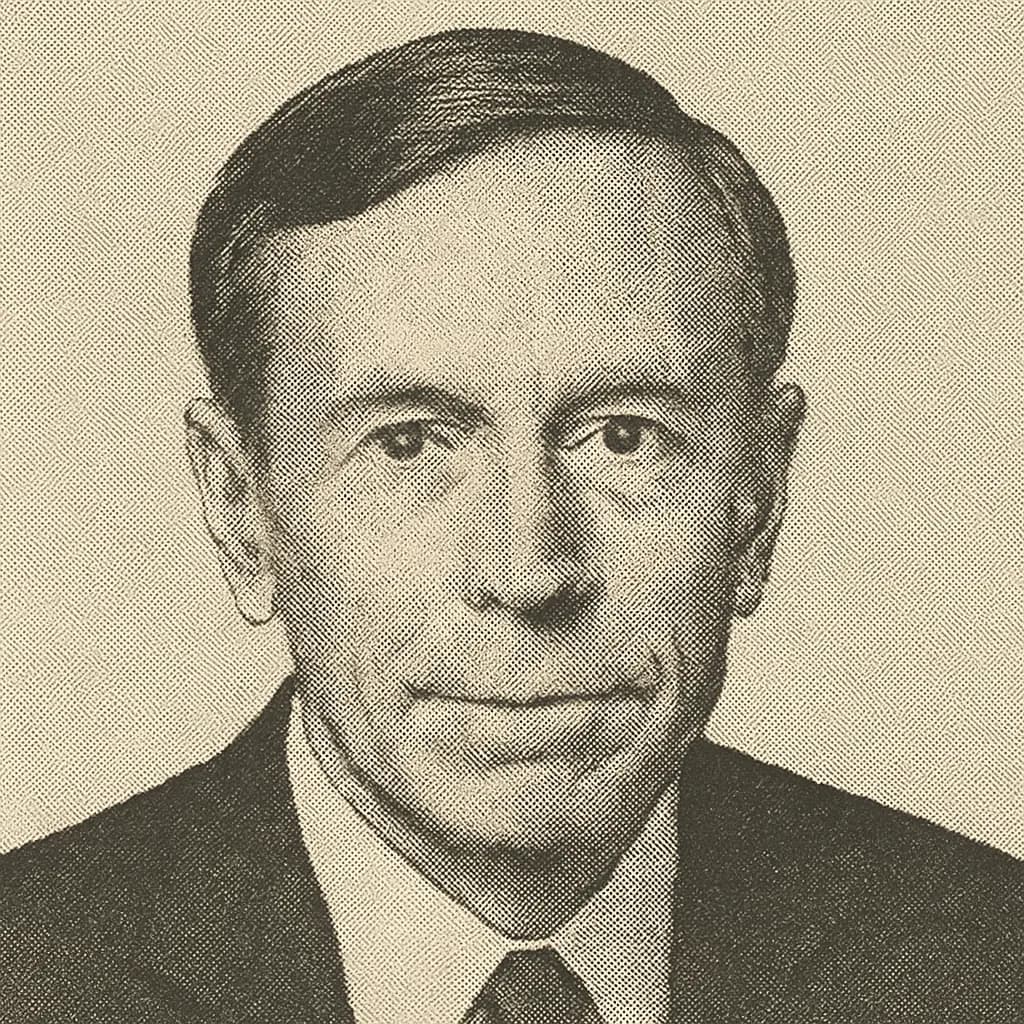

In Conversation with General David Petraeus

Strategy, culture, and reinvention across four decades of service.

In this conversation, General David Petraeus reflects on nearly four decades of service: guiding U.S. forces through the Surge in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan, and the evolution of modern warfare; why the "big ideas" determine success or failure; lessons on adaptability, grit, and culture; surviving near-death experiences; and how competitive spirit and his leadership framework drove him to lead one of the United States' most enduring institutions.

During a live-fire exercise at Fort Campbell, a soldier tripped and a rifle misfired, sending a 5.56 round straight through David Petraeus's chest. He had less than two minutes of life to spare. After emergency surgery, he demanded fifty push-ups to speed his discharge and returned to training weeks later. Years after that, a parachute collapsed a hundred feet above the ground and shattered his pelvis. Yet Petraeus will tell you those were not the moments that tested him most.

The real crucible came in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he faced explosions, casualties, and the burden of writing condolence letters almost daily. What prepared him started long before: the kid nicknamed Peaches who became a rare West Point triad, top of his class academically, varsity athlete, and cadet captain. Life, he realized early, was a competitive endeavor. Be the best individual and the best teammate, or do not expect to lead.

That mindset shaped his command of the 101st Airborne in 2003. In Mosul, Petraeus didn't just fight insurgents. He ran elections, restored services, rebuilt governance, and pushed reconciliation when national policy threatened to tear the country apart. His approach fused decades of counterinsurgency study with a simple conviction: if you get the big ideas wrong, every metric that follows goes wrong.

Those big ideas, get them right, communicate them relentlessly, oversee execution, and adapt continuously, became the strategic framework he carried from Iraq to Afghanistan to the CIA. He emphasizes culture as the compounding asset that allows institutions to endure, influencing everyday behavior as well as performance when stakes are highest. General Petraeus's career offers a rare vantage on how to align mission, metrics, and morale under pressure to adapt big ideas before the world adapts them for you. The most durable leaders are the ones who refuse to stand still.

On Near-Death Experiences and Early Determination

Gaurav Ahuja

To start on a personal note: you've had two very near-death experiences—once being shot in a training accident and another involving a parachute freefall accident in 2000. You've joked about doing fifty push-ups afterward, but take me back to those moments. What was going through your mind?

General Petraeus

In the shooting incident, it was a training accident—an accidental discharge by one of my own soldiers during a very aggressive live fire exercise. I was walking behind the unit with Brigadier General Jack Keane, then assistant division commander for operations of the 101st Airborne Division, which I would later command.

The exercise involved throwing grenades into bunkers. One soldier knocked out a bunker, came out, tripped, and his weapon discharged. A 5.56 round went right through my chest. Happily, I wasn't wearing a flak vest, which would have stopped the bullet but caused it to tumble inside if hit directly. This round made a small entry wound and a larger exit wound, nicking an artery but not severing it. Had it severed, I would have bled out in less than two minutes.

The pain was immense—I thought I'd been hit by a heavy machine gun. Shock set in quickly. I dropped to my knees, then went face down, worried they'd cut my load-bearing equipment, which was meticulously rigged. The medics acted fast, applying a plastic seal to my exit wound to prevent oxygen from escaping. A medevac helicopter arrived quickly, and General Keane held my hand the entire time, encouraging me.

At the hospital, doctors identified it as a sucking chest wound. They performed an emergency thoracic procedure, cutting an 'X' in my side and pushing in a chest tube with no anesthesia. It was the most painful experience of my life. Then I was flown to Vanderbilt Medical Center where Dr. Bill Frist, a top thoracic surgeon who later served as Senate Majority Leader, performed surgery to cauterize the artery nick and repair rib damage.

My recovery was rigorous. At one point I insisted on doing 50 push-ups to get discharged early; they eventually pulled the tubes and let me go home. I pushed myself to do laps with chest tubes attached, and later stalled activity for about 30 days due to a leak.

Gaurav Ahuja

You've stared death in the face with that shooting, and also the parachute accident.

General Petraeus

Yes, the parachute accident was caused by trying one too many turns and hitting an unexpected air current, forcing my canopy to dive. At 100 feet, you don't plane out. I hit hard, fracturing my pelvis and sustaining other injuries that required plates and screws. In some ways, it was more serious, but I recovered from both incidents.

But what I faced during operations in Iraq and Afghanistan was another type of staring death in the face—explosions, bombs, and casualties affected my sergeant major and me deeply. We attended many memorials and I wrote many condolence letters to families.

On Early Motivation: The Competitive Spirit

Gaurav Ahuja

Maybe take me a step further back. As a child, you were known as "Peaches" and seemed to be a "jack of all trades": a world-class athlete, a brainiac, and great social skills. What drove you to work so hard? Was it fear of failure or proving something to someone?

General Petraeus

At some point, I realized life is a competitive endeavor—you don't get a trophy just for showing up. At West Point, where the competition is intense, the three most prized qualities were academic excellence, physical ability, and leadership. I ranked in the top 5% academically in a tough pre-med major but chose infantry instead—I hadn't come to be a doctor, but a leader.

Athletically, I competed in varsity soccer and skiing, making the Eastern Collegiate Championships. Physically I was close to breaking obstacle course records and regularly passed rigorous PT tests.

In terms of leadership, I was one of two in my class with both a varsity letter and a cadet captain role. My approach was intensely competitive but also about being the best team player, which was critical. This balance was reflected in awards I received at Ranger School and Command and General Staff College where peer ratings mattered greatly.

I encouraged others to strive for personal excellence while also supporting their teams—being the best individual and the best teammate simultaneously. That, to me, defines motivated leadership.

On Holistic Leadership in Mosul and Counterinsurgency Insights

Gaurav Ahuja

Fast forwarding a bit, when you took command of the 101st Airborne in 2002 at Fort Campbell preparing for the Iraq War and later led operations in Mosul in 2003, your approach was holistic. It wasn't purely militaristic; there were local elections, restoration efforts, and a "Money as Ammunition Project." What inspired that nation-building strategy? Did you face pushback?

General Petraeus

It stemmed from extensive study and experience with counterinsurgency since I was a lieutenant—reading about the French in Indochina and Algeria, the British in Malaysia and Oman, and American efforts in Vietnam. I observed civil-military counterinsurgency campaigns firsthand in El Salvador, Colombia, and Peru while serving as Special Assistant to the Commander-in-Chief of U.S. Southern Command.

Also, in Bosnia, I was chief of operations for NATO's Stabilization Force and led clandestine joint task forces hunting war criminals post-9/11. That combined peacekeeping, counterterrorism, and civil efforts, which is a foundation for comprehensive counterinsurgency campaigns.

When we deployed the 101st Airborne in early 2003 and later operated in Mosul, we faced a growing insurgency with Islamist extremist elements. We focused on "clear, hold, build" operations combined with restoring security, services, and governance structures. We conducted the first local elections and established provincial councils balancing majority rule with minority rights—critical to avoiding sectarian dominance and fostering peace.

Two Coalition Provisional Authority decisions poured fuel on the fire: they disbanded the entire Iraqi military without pay and pushed de-Ba'athification down to 'level four,' which gutted the bureaucracy we needed to run the country. I asked for a shot at reconciliation—got a nod mid-flight on a miserably hot day with the helicopter doors pinned back—and we brought back thousands, actually tens of thousands, into provincial life and security roles.

There was significant preparation beforehand at the Joint Readiness Training Center with scenarios simulating guerrilla warfare and operations involving civilians, local leaders, and suicide bombers. Our division's previous peacekeeping and counterterrorism experience, combined with training rotations, prepared us better than heavier units for the complex environment.

On Testing Grit and Character Through Physical Fitness

Gaurav Ahuja

I've read that you used to test new recruits or team members on runs, pushing them hard to see who could keep up. Is there an equivalent of that in startups or business?

General Petraeus

Yes. When I commanded battalion and brigade-level units, many young officers wanted to join my units. I would interview them while conducting physical training—running a set 4-mile course at a fast pace with specific splits required. My version of an interview was a 4-mile run in 34 minutes—quarter-mile splits painted on Arden Street and a 3x5 card in my hand. I never ran slower than 34; I'd go as fast as the candidate wanted. If they couldn't keep up, it was a no-go. This showed who had commitment and grit.

More than physical tests, it was about how you manage effort and teamwork. I formalized training routines including warming up properly, multi-set exercises, and clear cadence calls, while allowing individual competition.

Every unit I commanded ran physical fitness competitions branded "Iron [Their Unit Name]," certified to precise standards with no ambiguity or arguments. For example, you touched your Adam's apple each rep, and the grader called 'up' and 'down' so there was no debate. Such tests put my finger on morale and abilities and helped maintain unit cohesion and readiness.

Even as a four-star during the surge in Iraq, I maintained a strict physical training regimen to keep connection with the troops and my leadership stamina.

The business analogue is a real deliverable on a short clock. I once handed a brand-new lawyer a heavy research task on a Thursday; he worked two nights, delivered early Saturday, and that performance started a partnership where he filled critical roles supporting combat and civil operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On the Four Tasks of Strategic Leadership

Gaurav Ahuja

Let's switch gears into your leadership framework. You are famous for advising many CEOs, and you have a famous "four core tasks" of strategic leadership. Could you summarize them?

General Petraeus

Certainly. These four tasks apply to leaders at any level, from startup founders to generals commanding hundreds of thousands.

Get the big ideas right. Craft the right strategy based on reality—not wishful thinking—understanding your own forces, the adversary, and all relevant terrain and human factors. An example of failure is Vietnam's prolonged misreading of the conflict; success requires getting this absolutely right. If you get the big ideas wrong, your metrics go wrong—we learned that the hard way with body counts in Vietnam.

Communicate the big ideas effectively throughout the organization and broader stakeholders. Everyone with a stake needs to understand the strategy and priorities—this was critical in Iraq with coalition partners, governments, and military. Communication has to reach everyone with a stake; otherwise people row in different directions.

Oversee implementation of the big ideas through layers of leadership. Set the example, design the organizational structures, recruit and retain top talent, apply appropriate metrics, and maintain a disciplined rhythm of meetings and reviews that keep focus tight. Implementation is architecture, talent, the right metrics, and a battle rhythm—for me that meant the 07:30 daily brief, small group, and smaller group.

Refine and adapt big ideas continuously as context shifts and new information appears. This is essential to avoid obsolescence as happened with Kodak, which failed to pivot despite owning digital patents—whereas Netflix refined their big ideas repeatedly, moving from DVD rental to streaming to original content production and major studio acquisitions.

These tasks repeat relentlessly at every stage of leadership. Failing at any one threatens overall success.

Gaurav Ahuja

The first time we met, you asked me, "What's the big idea?" I stumbled for a moment at the simplicity of the question, trying to explain the very business I was building in a single line. Why is it so hard for leaders to articulate their work clearly to the outside world?

General Petraeus

Because they haven't distilled the idea sufficiently. It seldom arises fully formed; it begins as a seed or kernel that grows iteratively with input from trusted colleagues. It should be a team sport. The refining process is like sculpting clay—many rounds of shaping until it becomes a clear, precise, and shared vision.

I advise leaders not to expect epiphanies but rather to develop and contest their ideas openly with others until they are crisp.

On Innovation and Nimbleness: Reinvention of the Army and Businesses

Gaurav Ahuja

Using the Netflix example earlier, you mentioned the importance of "killing your darlings." How has the Army reinvented itself to stay relevant amid technological changes—from tanks to cyber warfare?

General Petraeus

The Army has had to reinvent itself repeatedly to remain relevant, because the character of warfare changes even when its nature does not. Sometimes that reinvention comes from within, but often it requires strong external leadership, as you noted. The key is recognizing when legacy systems or concepts no longer match the realities on the ground.

Secretary Gates's decision to terminate the Comanche program is a classic example of that. The Army had invested enormous resources in it over many years, but the threat environment had shifted. We needed capabilities that could be fielded sooner, integrated more easily with joint systems, and supported more sustainably. Ending Comanche freed resources for platforms that delivered what we needed in Iraq and Afghanistan, such as unmanned aerial systems and upgrades to existing helicopters. It was a tough decision, but it preserved strategic relevance.

The shift from Humvees to Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles is another important case. When improvised explosive devices became the primary threat in Iraq, the flat-bottomed Humvee simply could not provide the protection required. Many of us in theater were very vocal about the need for V-shaped hulls and better survivability. Secretary Gates accelerated that transition dramatically. In fact, at one point, the delivery of MRAPs was the largest defense acquisition surge since World War II. That change saved countless lives and illustrates how quickly an organization can adapt when senior leadership prioritizes a requirement.

Great organizations do this. KKR, for example, recognized new big ideas. We bought an entire insurance company because we realized we could invest their money better. We moved into credit, real estate, infrastructure, and growth tech. Along the way, we left things by the side of the road that were less aligned.

Gaurav Ahuja

What about cyber and computing threats?

General Petraeus

What often gets overlooked is that cyber is not just about offense. It is also about resilience—protecting critical infrastructure, securing data, and ensuring continuity of operations even when adversaries attempt to penetrate or disrupt our systems. During my time as CIA Director, we saw firsthand how aggressive certain state and non-state actors were becoming in cyberspace. That drove a recognition across the national security community that cyber could no longer be a supporting function. It had to be a core competency.

Another major adaptation has been in signals intelligence, electronic warfare, and space-based capabilities. The Army is now deeply integrated with the broader joint approach to space and cyber, recognizing that communications, GPS, missile warning, and data transport are all contested. The growth of the 915th Cyber Warfare Battalion and the integration of cyber teams into brigade combat teams reflect that shift. It is no longer enough to have a handful of specialists in a distant headquarters—you need cyber and electronic warfare expertise alongside maneuver units.

You also see reinvention in the shift toward multi-domain operations, which integrates land, air, sea, cyber, and space. This is the Army acknowledging that future conflicts will require synchronized operations across all domains, enabled by data, artificial intelligence, and long-range precision fires. That is why the Army created the Multi-Domain Task Forces, which combine intelligence, cyber, electronic warfare, space capabilities, and long-range precision effects. These formations did not exist a decade ago, and now they are central to how the Army prepares for high-end conflict.

All of this reflects a broader truth: organizations stay relevant when they honestly assess emerging threats and invest in new capabilities even if it means divesting older ones.

On Building Enduring Culture: Lessons from the U.S. Army

Gaurav Ahuja

You've been steward of one of the most enduring organizations—the U.S. Army—whose core identity, "This We'll Defend," has remained consistent since 1775. How has the Army maintained such consistency over centuries in values, culture, and structure? How can companies build similar endurance?

General Petraeus

Every organization needs to distill and clearly define its culture iteratively, just like with the big ideas. In startups I've invested in, I've facilitated discussions where everyone around the table describes what culture they want. We collect everything, then refine it into a precise statement through open critique.

The Army reinforces culture every single day through rituals, training events, leadership interactions, and the small habits we insist on. Culture isn't a poster on a wall. It is what leaders reward, what they tolerate, and what they absolutely will not allow. As you mentioned, it is 250 years of these micro moments happening each day that creates a well defined culture that goes beyond the walls of the Army.

Gaurav Ahuja

What was most important when it came to the individual leaders regarding the consistency of culture?

General Petraeus

Culture survives centuries because leaders model it relentlessly. Soldiers watch what you do far more than what you say.

Leaders still sometimes fail to get big ideas right, but that's separate from culture clarity. Leadership training at every level—from pre-commissioning to war colleges—is extensive, but deciding who has the capacity for the big picture is vital. People like H.R. McMaster, who was outspoken and brilliant, exemplifies those who push boundaries and improve organizations despite sometimes ruffling feathers. Leadership promotion boards weigh these attributes carefully because strategic vision and leadership quality at the top shape outcomes.

Gaurav Ahuja

Do you have some memorable examples of setting this culture during your time in the Army?

General Petraeus

A few examples stand out because they show how culture is reinforced not by slogans but by daily actions, especially under demanding conditions.

During the Surge in Iraq, I spent a great deal of time visiting small combat outposts and joint security stations. What always struck me was how consistently junior leaders embodied the values we emphasized. At one outpost in Baghdad, a young platoon leader was meeting with local sheikhs and community representatives. Scenes like that were repeated across the country. Those engagements were not directed by a script. They were simply leaders applying the principles we had long emphasized: treat people with respect, build relationships, and operate with tactical patience.

Another example comes from my time commanding the 101st Airborne Division. The division has long maintained rigorous standards for training, including at the Air Assault School at Fort Campbell. What mattered most was the consistency: every class, every training cycle, every inspection reinforced the same expectations of discipline, attention to detail, and mastery of one's craft.

Gaurav Ahuja

Take me further back. Were there moments in the 250 year history of the Army where it seemed like there was existential risk? What were those great stories that get told around the metaphorical fire in Army circles?

General Petraeus

There are several periods in the Army's history that are taught again and again because they remind each generation that our culture was shaped under extraordinary pressure.

One of the earliest examples is the winter at Valley Forge in 1777 and 1778. The Continental Army was in desperate condition. But what is emphasized in our professional military education is not just the hardship; it is the impact of Baron von Steuben's training. He introduced standardized drills and discipline at a moment when the Army could have disintegrated. His work forged a professional fighting force from a collection of militias.

Another moment that is often referenced is the post-Vietnam era. The Army had enormous challenges: morale issues, discipline problems, and the transition to an all-volunteer force. What stands out is the institutional willingness to confront shortcomings honestly. It is a reminder that culture endures not because an organization is perfect, but because it has the humility and discipline to learn and adapt.

What ties these periods together is that the Army's leaders returned to core values and enforced them through actions, not rhetoric. They faced conditions that could have fractured the institution, yet the response was always the same: strengthen standards, invest in leader development, and recommit to the profession's foundational principles. Those are the stories every generation learns, because they remind us that culture is not inherited automatically. It has to be reaffirmed, sometimes rebuilt, and always lived.

The opinions expressed in this newsletter are my own, subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect those of Timeless Partners, LLC (“Timeless Partners”). More...

Nothing in this newsletter should be interpreted as investment advice, research, or valuation judgment. This newsletter is not intended to, and does not, relate specifically to any investment strategy or product that Timeless Partners offers. Any strategy discussed herein may be unsuitable for investors depending on their specific objectives and situation. Investing involves risk and there can be no assurance that an investment strategy will be successful. Links to external websites are for convenience only. Neither I, nor Timeless Partners, is responsible for the content or use of such sites. Information provided herein, including any projections or forward-looking statements, targets, forecasts, or expectations, is only current as of the publication date and may become outdated due to subsequent events. The accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information cannot be guaranteed, and neither I, nor Timeless Partners, assume any duty to update this newsletter. Actual events or outcomes may differ significantly from those contemplated herein. It should not be assumed that either I or Timeless Partners has made or will make investment recommendations in the future that are consistent with the views expressed herein. We may make investment recommendations, hold positions, or engage in transactions that are inconsistent with the information and views expressed herein. Moreover, it should not be assumed that any security, instrument, or company identified in the newsletter is a current, past, or potential portfolio holding of mine or of Timeless Partners, and no recommendation is made as to the purchase, sale, or other action with respect to such security, instrument, or company. Neither I, nor Timeless Partners, make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness or fairness of the information contained in this newsletter and no responsibility or liability is accepted for any such information. By accessing this newsletter, the reader acknowledges its understanding and acceptance of the foregoing statement.